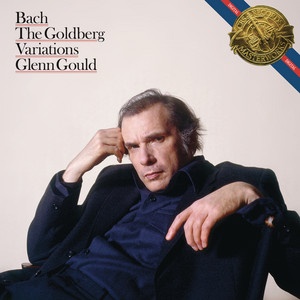

J.S. Bach: The Goldberg Variations

by Glenn Gould

Review

**★★★★★**

In 1955, a gangly 22-year-old Canadian pianist walked into Columbia Records' 30th Street Studio in New York with a peculiar collection of demands: a low chair that put his knees practically under his chin, a glass of water, a bottle of pills, and several towels for his sweating hands. What emerged from those sessions would fundamentally alter how the world understood both Johann Sebastian Bach and the very nature of piano performance itself.

Glenn Gould's debut recording of Bach's Goldberg Variations didn't just announce the arrival of a major talent – it detonated like a sonic bomb in the stuffy world of classical music. Here was baroque music stripped of its powdered-wig pretensions and reimagined as something urgent, modern, and startlingly alive. The album's success was so immediate and overwhelming that it remained in Columbia's catalogue for decades, selling over 100,000 copies in its first three years alone – virtually unheard of for a classical debut.

The Goldberg Variations themselves occupy a unique place in Bach's catalogue. Originally composed in 1741 as keyboard exercises – supposedly to cure an insomniac count's sleepless nights – the work consists of an aria followed by thirty variations, each more intricate than the last, before returning to the opening theme. It's music of mathematical precision and emotional depth, requiring both technical mastery and interpretive vision. Before Gould, most pianists approached it with reverent caution, if they attempted it at all.

Gould obliterated that reverence. His interpretation crackles with electricity from the opening aria, played with a clarity and intimacy that makes Bach's counterpoint sing like chamber music. Where others heard academic exercise, Gould found jazz-like syncopation, romantic yearning, and modernist angularity. His tempo choices were radical – some variations taken at breakneck speed, others stretched into meditative slow-motion – yet every decision feels inevitable, as if Bach himself were whispering instructions.

The album's most revelatory moments come in variations like the haunting 25th, where Gould transforms what's often treated as a stately sarabande into something that anticipates Bill Evans' impressionistic jazz piano by decades. His handling of the canonic variations (numbers 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, and 27) reveals Bach's architectural genius while making each feel like a spontaneous conversation between voices. The explosive 29th variation practically leaps from the speakers with its cascading arpeggios, while the final 30th – a quodlibet that quotes German folk songs – becomes a joyous celebration rather than mere technical display.

Gould's physical approach was as revolutionary as his interpretive one. He sang along audibly (much to his producers' initial horror), conducted himself with his free hand, and attacked the keyboard with a combination of delicacy and percussive force that extracted colours from the piano that seemed almost orchestral. His famous humming, barely audible on this early recording but destined to become more prominent, adds an oddly human dimension to the mathematical precision of Bach's writing.

The recording quality itself deserves mention – Columbia's engineers captured Gould's performance with a clarity and presence that remains stunning nearly seventy years later. Every note rings with crystalline definition, allowing listeners to follow Bach's intricate voice-leading with unprecedented ease. The studio's acoustics provide just enough warmth to prevent the precision from feeling clinical.

The album's impact was seismic and lasting. It single-handedly revived interest in Bach's keyboard works, inspired countless pianists to reconsider baroque performance practice, and established Gould as classical music's first genuine recording star. More importantly, it proved that historical music could speak with contemporary urgency when filtered through an uncompromising artistic vision.

Gould would return to the Goldberg Variations one final time in 1981, just months before his death, creating a slower, more introspective interpretation that served as both artistic summation and farewell. Yet this 1955 recording remains the more essential document – a young genius announcing himself to the world with music that sounds as fresh and startling today as it did seven decades ago.

In an era when classical music often struggles for relevance, Gould's Goldberg Variations stands as proof that the right artist can make any music timeless. It's not just one of the greatest classical recordings ever made; it's one of the most important musical statements of the 20th century, perio

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.