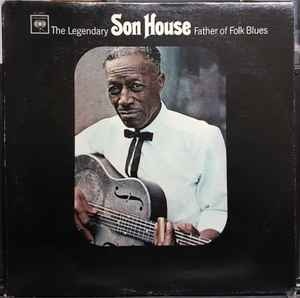

Father Of Folk Blues

by Son House

Review

In the pantheon of blues legends, few figures loom as large or as mysteriously as Eddie "Son" House, and nowhere is his towering influence more evident than on the seminal 1965 album "Father of Folk Blues." This isn't just a collection of songs – it's an archaeological dig into the very DNA of American music, a raw nerve ending exposed after decades of dormancy.

The story behind this album reads like something out of a blues mythology textbook. House had virtually vanished from the music scene by the 1940s, working railroad jobs and preaching in upstate New York, his revolutionary Delta blues style seemingly lost to time. Then, in 1964, a group of young white blues enthusiasts – the kind of obsessive record collectors who treat 78 RPM shellac like religious artifacts – tracked him down in Rochester. What they found was a man who had been out of the game for over two decades, his fingers stiff, his voice weathered, but his soul still burning with that primal fire that had once mesmerized a young Robert Johnson.

The recording sessions that produced "Father of Folk Blues" were nothing short of miraculous. House, now in his sixties, had to relearn songs he'd written decades earlier, muscle memory slowly returning as he coaxed those ancient melodies from his National steel guitar. The result is an album that sounds like it was beamed in from another dimension – one where pain and redemption dance together in perfect, terrible harmony.

House's musical style defies easy categorization, even within the blues tradition. This is Delta blues stripped down to its absolute essence, but calling it "folk" almost seems like an insult to its raw power. His guitar work is percussive and hypnotic, using the steel strings and metal body of his National guitar to create sounds that seem to emerge from the Mississippi mud itself. His voice, meanwhile, operates on a completely different plane – sometimes a whisper, sometimes a roar, always carrying the weight of lived experience that no amount of technical training could replicate.

The album's crown jewel is undoubtedly "Death Letter Blues," a six-minute masterpiece that stands as one of the most emotionally devastating recordings in American music. House's voice cracks and soars as he recounts receiving news of his lover's death, while his guitar creates a rhythmic undertow that pulls listeners into the depths of his grief. It's the kind of performance that makes you understand why the blues exists in the first place – as a vessel for emotions too large and too complex for ordinary conversation.

"Grinnin' in Your Face" showcases another side of House's genius, a haunting a cappella warning about false friends that builds tension through nothing but vocal dynamics and hand claps. Meanwhile, "John the Revelator" transforms biblical imagery into something that feels both ancient and urgently contemporary, House's delivery suggesting he's channeling messages from both the pulpit and the juke joint.

Perhaps most remarkably, "Levee Camp Moan" captures House in full storyteller mode, his voice painting pictures of backbreaking labor and systemic oppression with an immediacy that makes the listener feel like they're sitting on a front porch in 1930s Mississippi. The song builds and releases tension like a master class in dynamics, proving that House understood the architecture of emotion better than most conservatory-trained composers.

The album's impact on the folk revival movement of the 1960s cannot be overstated. Suddenly, coffee house singers who had been performing sanitized versions of traditional songs were confronted with the real thing – raw, uncompromising, and absolutely authentic. Artists like Jack White, who would later collaborate with House's spiritual descendants, have cited this album as a foundational influence, and it's easy to hear why.

Today, "Father of Folk Blues" stands as more than just a historical document – it's a living, breathing testament to the power of authentic expression. In an era of Auto-Tune and digital perfection, House's weathered voice and occasionally fumbled chord changes feel revolutionary. This is music that couldn't be manufactured in a focus group or engineered in a laboratory. It's the sound of one man's soul, preserved in amber for future generations to discover and rediscover.

The album remains essential listening for anyone seeking to understand not just the blues, but American music itself. Son House didn't just influence the folk blues – he practically invented it, and this album is his definitive statement.

Listen

Login to add to your collection and write a review.

User reviews

- No user reviews yet.