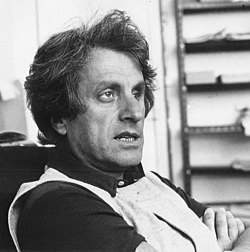

Iannis Xenakis

Biography

In the pantheon of 20th-century musical revolutionaries, few figures loom as large or as intimidatingly brilliant as Iannis Xenakis, a man who literally helped build the modern world before tearing apart everything we thought we knew about sound. Born in Romania in 1922 to Greek parents, Xenakis would become the mad scientist of contemporary classical music, wielding mathematics like a weapon against musical convention and creating sonic landscapes that sound like the birth and death of galaxies.

Before he ever touched a note, Xenakis was already living a life that would make most rock stars weep with envy. After studying engineering in Athens, he joined the Communist resistance during World War II, fighting against both the Nazis and later the British-backed government forces. In 1947, a British shell fragment nearly killed him, leaving him blind in one eye and bearing facial scars that would mark him for life. Facing a death sentence from the Greek government, he fled to Paris with nothing but his engineering degree and a head full of revolutionary ideas.

It was in Paris that Xenakis began his unlikely journey from structural engineer to sonic architect. Working for the legendary Le Corbusier, he helped design some of the most iconic buildings of the modern era, including the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair – a building that looked like it had crash-landed from another planet. But while his hands were shaping concrete and steel, his mind was plotting the overthrow of musical orthodoxy.

Xenakis didn't just compose music; he engineered it. Armed with probability theory, game theory, and set theory, he approached composition like he was solving the mysteries of the universe. His breakthrough came with "Metastaseis" in 1954, a piece that translated architectural principles into sound, creating massive sonic structures that seemed to defy the laws of physics. The score looked like abstract art, with glissandos sweeping across the page like mathematical equations given voice.

What made Xenakis truly dangerous was his complete disregard for musical tradition. While other avant-garde composers were still tiptoeing around tonality, Xenakis grabbed a sledgehammer and went to work. His "Pithoprakta" used probability theory to determine when and how instruments would play, creating music that sounded like controlled chaos – or perhaps chaotic control. He didn't just break rules; he rewrote the entire rulebook using algorithms and computer programs.

The man was obsessed with texture and mass, treating orchestras like vast sonic sculptures. His percussion works, particularly "Psappha" and "Rebonds," turned drummers into athletes, demanding superhuman endurance and precision. These weren't just compositions; they were gladiatorial contests between human performers and mathematical precision. Musicians approached his scores with the same mixture of terror and respect that mountaineers reserve for Everest.

Xenakis pioneered electronic music with the same revolutionary fervor he brought to acoustic composition. His "Concrete PH," created from recordings of burning charcoal, transformed everyday sounds into alien transmissions. He developed the UPIC system, a computer program that could translate drawings directly into sound, essentially allowing composers to paint with audio. This wasn't just innovation; it was musical prophecy, predicting the digital revolution decades before it arrived.

His influence extends far beyond the concert hall. Rock musicians from Frank Zappa to Thom Yorke have cited his work as inspirational, while film composers regularly pilfer his techniques for science fiction soundtracks. Video game designers and electronic music producers continue to mine his innovations, finding new ways to weaponize his mathematical approaches to sound.

The accolades followed: the Polar Music Prize, UNESCO's International Music Prize, and recognition from institutions worldwide. But perhaps his greatest achievement was proving that music could be both intellectually rigorous and emotionally devastating. His pieces don't just challenge listeners; they transform them, creating experiences that feel like witnessing the formation of new worlds.

Xenakis died in 2001, but his legacy continues to mutate and evolve. In an age of algorithmic composition and AI-generated music, he seems less like a historical figure and more like a time traveler who returned to show us the future. His music remains as challenging and uncompromising as ever – a testament to the power of treating sound not as entertainment, but as a force of nature that can reshape consciousness itself. In the end, Xenakis didn't just compose music; he composed the future.

Albums

- No albums yet.